J.R.R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion contains a beautiful depiction of the world’s creation through music by Eru Ilúvatar and his choir of Ainur. It has passionate love stories, an Oedipal tale of woe, and theological conundrums aplenty.

The Hobbit, by contrast, contains:

- A character who invents the game of golf by knocking the head of the goblin Golfimbul into a rabbit-hole

- Dopey trolls named William, Bert, and Tom, who speak in Cockney

- Goblins who sing doggerel verse like “Clap! Snap! The black crack! / Grip, grab! Pinch, nab! / And down, down to Goblin-town / You go, my lad!”

- Silly Rivendell elves who giggle too much and sing verses like “O! tril-lil-lil-lolly / the valley is jolly, / ha! ha!”

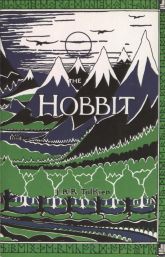

If you’re going to read the complete works of Tolkien properly, you definitely should not follow The Silmarillion with The Hobbit. (Read my take on The Silmarillion.) I was planning to read The Children of Húrin or Unfinished Tales next, but I don’t own copies of these books at the moment. So rather than get off my duff to go buy them, I decided to read the next Tolkien novel I had at hand, and now I wish I hadn’t. The works are so unalike in tone they don’t even seem to be written by the same person, much less take place in the same world.

If you’re going to read the complete works of Tolkien properly, you definitely should not follow The Silmarillion with The Hobbit. (Read my take on The Silmarillion.) I was planning to read The Children of Húrin or Unfinished Tales next, but I don’t own copies of these books at the moment. So rather than get off my duff to go buy them, I decided to read the next Tolkien novel I had at hand, and now I wish I hadn’t. The works are so unalike in tone they don’t even seem to be written by the same person, much less take place in the same world.

Originally, Tolkien’s intent was to keep The Hobbit a light children’s fable with a few cameo appearances from the characters and places of his Middle Earth mythology. And so Elrond has a token role, and the swords of Gandalf and Thorin were made in Gondolin, and there’s a passage about how the Mirkwood elves were “descended from the ancient tribes that never went to Faerie in the West.” After giving a brief child’s overview of the difference between Light Elves and Dark Elves, Tolkien concludes unhelpfully, “Still elves they were and remain, and that is Good People.”

There’s a lot of this irritating condescension throughout the course of The Hobbit, and at several points, I was tempted to just throw the book down and move on. The plot for the first half of the book goes something like this: Gandalf the wizard picks Bilbo Baggins, a hobbit of no special ability or importance, to accompany a band of dwarves on a quest, for no apparent reason whatsoever. Dwarves, wizard, and hobbit have unconnected adventure after unconnected adventure, wherein Bilbo largely sits back and does nothing. Bilbo stumbles on a magic ring by sheer luck, which allows him to sit around and smirk at the dwarves while still doing nothing.

Then something interesting happens: about halfway through the book, The Hobbit grows up.

Suddenly Bilbo is thrust into a position of responsibility. And then not only must he make the standard decisions that any hero must make — should I take responsibility? should I take command? should I risk myself for the sake of others? — but by the end he gets thrust into a number of more complex moral dilemmas as well.

And this is where The Hobbit ventures into territory that’s most peculiar for a children’s novel. Whereas the first two-thirds of the book is quite simplistic, the last third is strangely psychological and postmodern. I hadn’t remembered this from my previous readings, and I wish I could give Tolkien credit for planning such ambiguity from the beginning. But the book doesn’t read that way. It reads more like a tale that’s quite content to bumble along for a while until Tolkien discovers some use for it.

In the book’s last third, the dragon Smaug, until now just a convenient cipher of evil, turns out to be strangely human. He’s hoarding Thorin’s ancient treasure — but as Tolkien clearly points out, he doesn’t really have much use for it. It’s not like Smaug can cart some of that gold down to Laketown and go on a spending spree. So why does he hang on to it? Here Tolkien starts talking about how the wealth casts a “spell” and an “enchantment” on all who see it. Why does Smaug guard the treasure? Because he can’t help himself. He’s compelled to.

But not only is the treasure not much use to Smaug — it’s not much use to Bilbo or Thorin’s company either. “Had you never thought of the catch?” the dragon tells Bilbo. “A fourteenth share, I suppose, or something like it, those were the terms, eh? But what about delivery? What about cartage? What about armed guards and tolls?” Men, elves, dwarves, goblins, and dragon were all living in a nice-if-imperfect equilibrium before Thorin’s arrival, with the gold safely tucked away in legend. But now suddenly the arrival of Thorin’s company and their lust for gold has thrown everything into chaos.

But not only is the treasure not much use to Smaug — it’s not much use to Bilbo or Thorin’s company either. “Had you never thought of the catch?” the dragon tells Bilbo. “A fourteenth share, I suppose, or something like it, those were the terms, eh? But what about delivery? What about cartage? What about armed guards and tolls?” Men, elves, dwarves, goblins, and dragon were all living in a nice-if-imperfect equilibrium before Thorin’s arrival, with the gold safely tucked away in legend. But now suddenly the arrival of Thorin’s company and their lust for gold has thrown everything into chaos.

Once the dragon has been disposed of (thanks to the much-too-convenient appearance of an English-speaking bird), things get even more unsettled. Not only do the men, elves, and dwarves all begin squabbling over who deserves what share of the money — but Tolkien goes out of his way to give everyone a pretty damn good claim too. Men deserve a share because their gold is mixed in the hoard, and they slew the dragon, after all; the elves deserve a share because they stepped in to aid the Laketown people after their town was destroyed, at great personal risk to themselves; and the dwarves deserve a share because they inherited it in the first place.

And it’s here where Bilbo makes the redemptive move that proves he’s a hero and not just a bystander. He pilfers Thorin’s prized Arkleseizure Arkenstone jewel and tries to use it to bring a peaceful settlement to the conflict. It’s a moral labyrinth that’s quite beyond the prepubescent audience the book’s opening chapters are written for: Bilbo steals something valuable that’s not his, lies to and betrays his friends, and then gives it away to provide the men and elves bargaining leverage to secure peace.

Having made his point about the corrosiveness of wealth and the moral greyness that clouds everything (cf. the oath of Fëanor from The Silmarillion), Tolkien decides he’s had enough. He quickly wraps things up with a rather anti-climactic battle at the end, which reads like an excerpt from a more adult work altogether, and Bilbo goes home.

In fact, the whole novel reads like a condensed, simplified version of The Lord of the Rings. Both works have a quest that begins with moral clarity and ends in ethical confusion; a seductive evil at the heart of the quest that warps the minds of those around it; and hobbits who begin the tale as small, insignificant players but eventually find a place on the wider stage. Some of the principle characters are conquered by evil and pay for it with their lives; others persist to the end because of their innate humbleness and resistance to greed.

Whether fortunately or unfortunately, Tolkien wasted enormous amounts of time and energy later in life trying to smooth out the inconsistencies between his three major and somewhat incompatible works (The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion). He went back and made a few alterations to the “Riddles in the Dark” chapter where Bilbo encounters Gollum and finds the One Ring. And he very cleverly hinted in the marginalia of LOTR that Bilbo Baggins himself was responsible for writing The Hobbit — thus providing a convenient explanation for the jocular tone. The Hobbit therefore isn’t just a children’s tale, but a hobbit children’s tale, told by a hobbit, and told by a somewhat self-important hobbit who isn’t exactly a disinterested third party.

So there’s The Hobbit, in a nutshell: a pleasant children’s tale that morphs suddenly into an unsettling adult one, with some clumsy footwork to try and justify the shift. If Tolkien had never finished The Lord of the Rings and his son had never posthumously published The Silmarillion, we might be remembering The Hobbit as an odd, yet charming, story that began as high adventure and found postmodernism along the way.

So there’s The Hobbit, in a nutshell: a pleasant children’s tale that morphs suddenly into an unsettling adult one, with some clumsy footwork to try and justify the shift. If Tolkien had never finished The Lord of the Rings and his son had never posthumously published The Silmarillion, we might be remembering The Hobbit as an odd, yet charming, story that began as high adventure and found postmodernism along the way.

***

(Actually, if you want to think about it another way, The Hobbit provides a nice little allegory to the U.S. situation in Iraq. Bush/Thorin decides he’s going to slay the dragon/Saddam Hussein. The dragon/Saddam warns that while evil, he’s actually a stabilizing factor in the region, and that his death will only cause chaos. Once the dragon/Saddam is gone, Bilbo Baggins/Colin Powell attempts to find a peaceful compromise, only to be tossed out on his ear by Bush/Thorin. Previously subdued rival factions — elves/Sunnis, men/Shiites, dwarves/Kurds — begin bashing each other to pieces. Meanwhile, foreign infiltrators — goblins/Iranians, wargs/Syrians, eagles/British — pour over the border…. How far do you want me to go with this?)